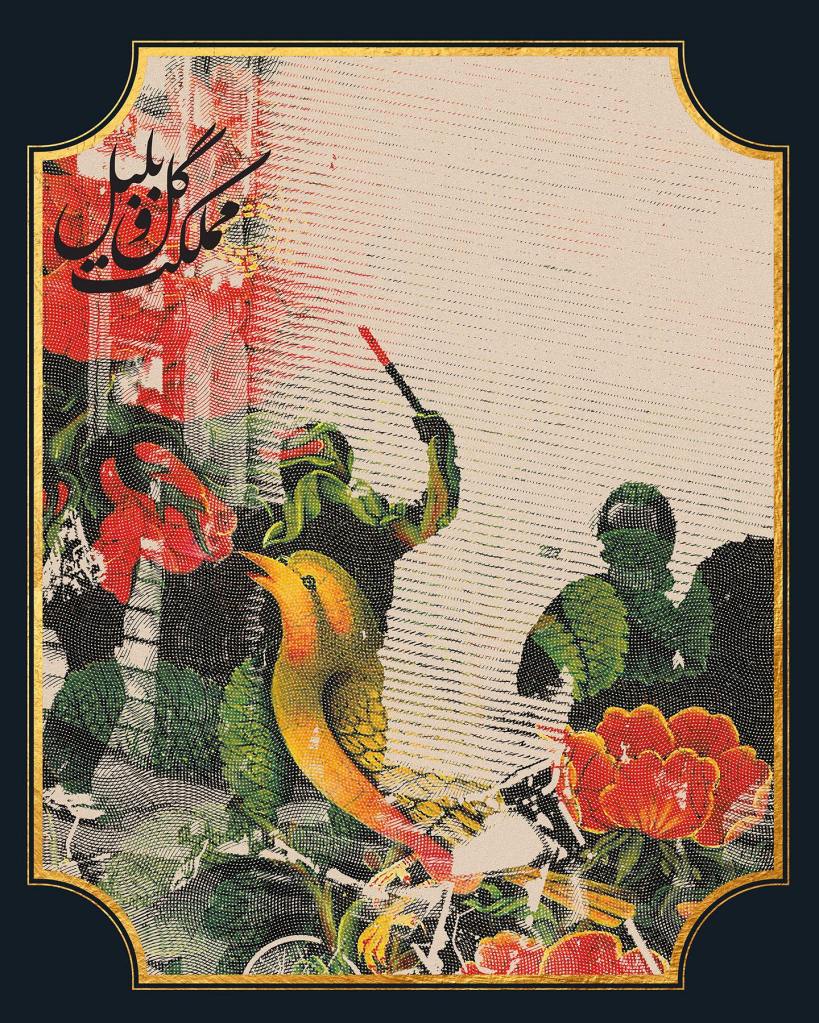

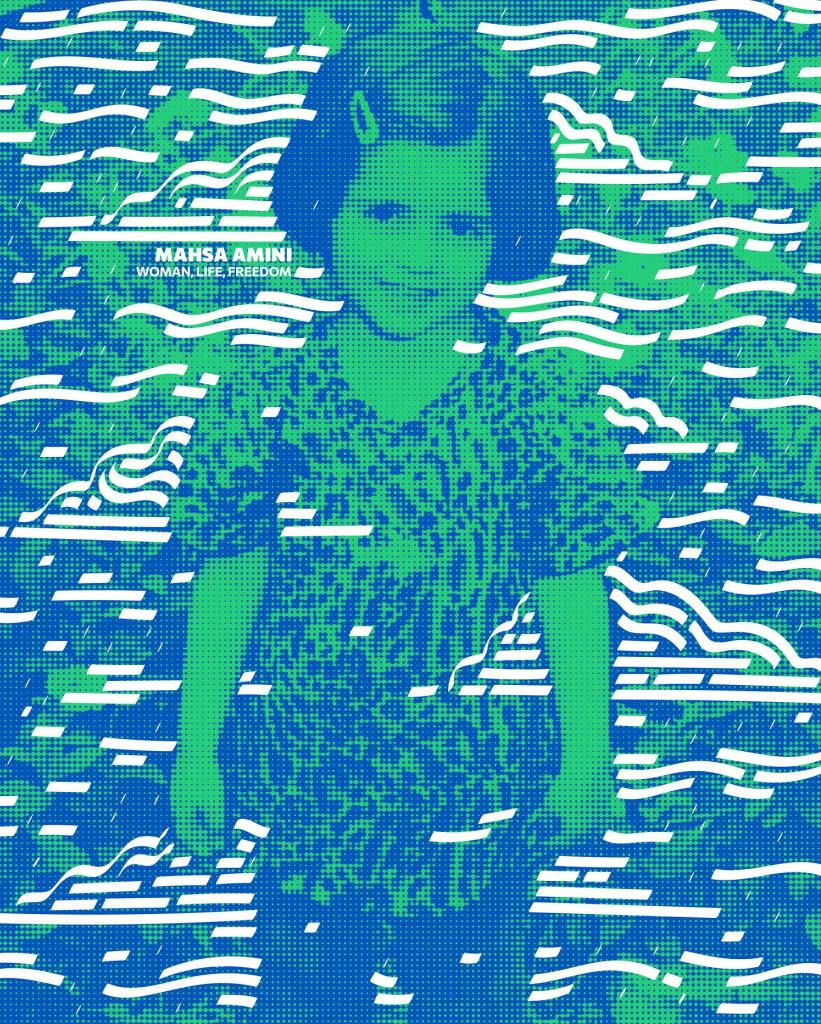

On September 16 2022, news emerged of the murder of a young woman in Iranian police custody. Jina Amini, who was also known as Mahsa, reflecting state discrimination against her Kurdish mother tongue, became a symbol for a mass popular movement. Four Iranian activists reflect on the state of the uprising, one year on.

This is an article from the current issue of Middle East Solidarity magazine. Download the full issue here, or order your print copy from Bookmarks Bookshop.

Azadeh Neman

After the violent crackdown and murderous response from the regime to the Mahsa revolution, the nature of the movement on the streets changed. Organising on the streets became so difficult and dangerous.

So many activists have been killed, over the years as well as during the past year, so many young lives destroyed or taken from their families.

The extrajudicial killings, which the government openly admits, are merciless in targeting activists and often their whole families, including children.

The resistance continues in the streets of Kurdistan and Balochistan, although the repression is extreme. In Balochistan two children were direct victims of the regime violence during WLF protests while many are losing their lives while carrying heavy cargo across the border to earn a meagre living.

There is desperate and deliberate poverty in both provinces with its social costs felt especially in Balochistan, where underage marriage for girls is very common. Perhaps people here feel they have nothing to lose. In Kurdistan too, where Mahsa (Jina) Amini came from, they are used to high levels of repression, the resistance has never died there and WLF protests gave it new life. Despite its brutal acts, the regime has failed to quell the movement.

As far as the general movement is concerned the gains were never going to be sustained, the aim was always regime change. We have to have fundamental changes especially in the constitution as is mentioned in the Charter of Minimum Demands. The message is still coming out on YouTube and Telegram channels (in the absence of any established foreign media) which keeps the government worried. The unions, or syndicates, are still working to organise and mobilise, but not on the streets. The movement is alive and has shifted to a slow but continuous struggle for fundamental change.

In September 2023, this year, as the anniversary of Mahsa’s murder approached, the regime started arresting Mahsa’s family members , teachers, union members, their lawyers, and activists. The regime feared any demonstrations and a re-awakening of protest on 16 September.

They ordered the closing down of schools and universities for a month to avoid opening in September. This demonstrates how weak the regime feels at this moment.

In North London where flyers for the protests on September 16 were distributed in some shops and restaurants, those businesses were attacked and their windows broken by regime supporters. This clearly shows the regime is even frightened of the movement outside Iran, in the diaspora.

The campaign from teachers has continued. There is a letter demanding the release of political prisoners, amongst them WLF protesters. This has been initiated by the teacher’s union, the CCITTA. The government has been running a campaign of terror and harassment against teachers with forced retirement, demotions, which means they will lose their salaries.

At the moment 36 percent of Iranian teachers receive a salary that by the Iranian regime’s admission is 60 percent below the poverty line. Demotion means their salary will be 10 percent of the poverty line in Iran. Many teachers have a second job just to be able to feed their families.

If a teacher’s ideology doesn’t align with the regime then they risk a severely reduced salary or job loss. Even in the face of these measures by early September, 36,000 teachers have signed the protest letter. This is a testament to the resilience of the movement and shows that people have not given up and are determined to keep the pressure on the government.

This is why it is so important that all workers’ unions, especially those for teachers like the NEU, clearly state their solidarity with their Iranian counterparts. As ordinary people our power lies in solidarity with each other, especially with those who are risking their freedom, and sometimes their lives, to secure a nation’s basic human rights.

Azadeh Neman is an International Solidarity Officer with North Kent NEU

Haydeh Ravesh

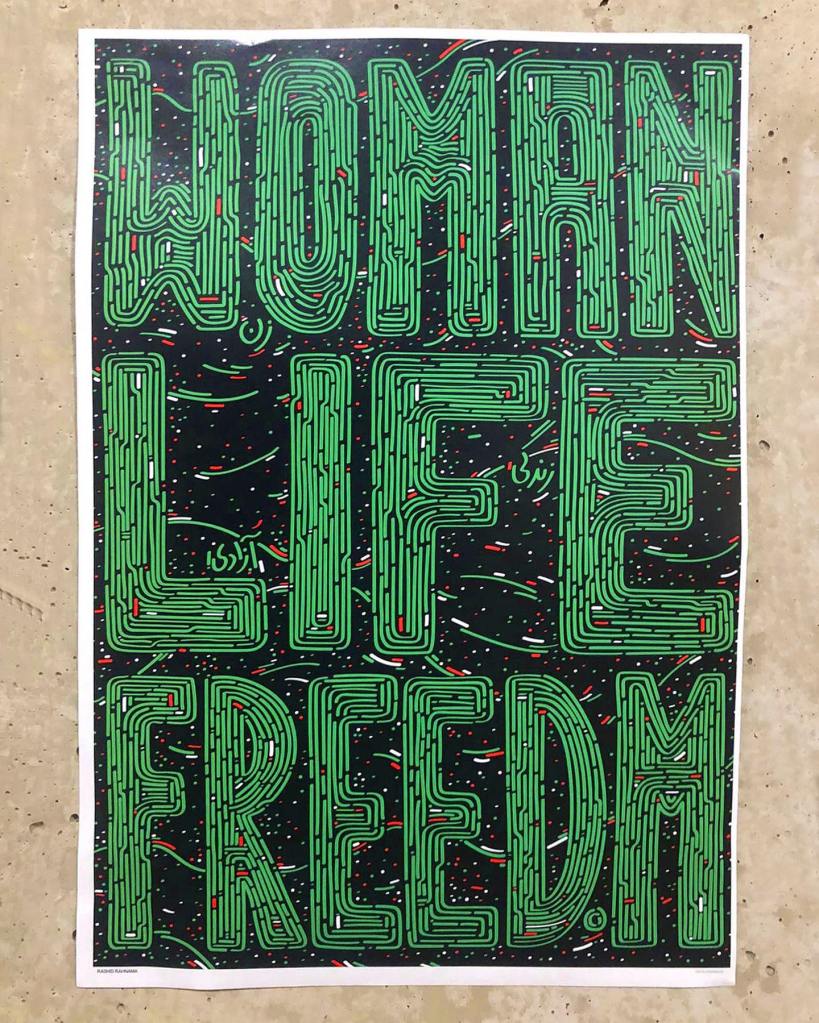

Since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, we have witnessed several social and political protest movements against the totalitarian Islamic regime. The latest rising, which has come to be known as the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, began in September 2022.

The first sparks of a lasting movement were triggered with the arrest and subsequent death of a young Kurdish woman for not observing the code of covering hair (hijab). The event ignited a widespread social protest movement, especially among youth in high schools and universities demanding women’s rights and political freedom.

This uprising was initially received with a great deal of enthusiasm by people hoping that the movement could unleash the social forces necessary for fundamental change – particularly regarding women’s rights under clerical rule. At a time when the Iranian economy was in a state of endemic crisis, increasing unemployment and poverty, soaring inflation and repressive anti-union policies gave hope that the regime would not stay intact for long. Some scholars had predicted that internal growing dissatisfaction, coupled with political support from the Iranian diaspora, could generate the energy required for the movement to sustain its power. Yet even though daily practices around wearing hijab have shifted towards further informal freedoms, the uprising faltered and has not yet led to any systemic change in Iranian politics.

Assessing the protest movement’s partial failure can be attributed to a wide variety of causes, but this brief outline concerns itself with three fundamental aspects. First, the number of protestors in the streets was insufficient to claim national coverage; the movement did not have broad support of country-wide risings. Second, the young activist groups were not able to acquire cross-

generational support and deepen their appeal as a legitimate alternative to the status quo. Third, the protest movement could not break class barriers to attract groups from other socio-economic layers of Iranian society.

Although initially large-scale demonstrations were held in Tehran and Iran’s larger cities, the protest movement did not spread widely to towns and villages. The notion of women living a life of freedom brought potentially major controversial issues onto the political agenda, and the residents of the villages, especially rural women, did not identify with the slogans of the movement.

Protest slogans and methods were centred on social and civil liberties. People in small towns and rural areas of Iran are mostly religious-minded and generally hold conservative values. They are also facing severe environmental and financial problems due to the ongoing economic crises. These elements meant there was little rural sympathy and companionship with the protest movement.

The composition of the protestors was a major factor in the partial failure of the movement. The social base of the protest movement comprised mainly young people, predominantly well-educated urban semi-affluent middle classes with a modern outlook. Although there were some demonstrations and protests in deprived and poor areas, especially in Tehran, they did not spread sufficiently to create a national movement. The lack of active participation of the working class and the unemployed, especially in the margins of big cities and towns, has greatly weakened the uprising’s longevity and its coverage of Iran.

Furthermore, the age-composition of protestors was around 16 to 25 years old. They had very little political experience in organising or leading a national protest movement. The older generations often expressed sympathy with demonstrators and their demands but nevertheless mostly they stayed away from direct participation in the movement.

From a sociological point of view, the active engagement and support of 25- to 45-year-olds plays a crucial role in bringing social change and determining the outcomes of a protest movement. Their hesitation to join the movement had detrimental effects in achieving the goals of the risings. It is interesting to note that throughout the protest period, the regime maintained a united front and no support was offered from big businesses or workers in the form of strikes. The protest movement could not attract wider segments of the population.

Some scholars have suggested that about three-quarter of people showed sympathies with the demonstrators but did not actively participate or support the movement. A successful uprising requires both a long-term strategy and short-term tactics as well as a clearly defined plan for a future government that can respond to the aspirations of the people.

It must also be inclusive to embrace the needs and interests of a majority of the population. This involves reliable and consistent leadership and a capacity to utilise events (as tactical means) for deepening the goals of the movement. On both accounts the movement failed to attract a large enough population who were dissatisfied with government policies and mismanagement of the economy, and the movement did not have a socio-political programme for the future of the country. One of the major failures of the protest movement was its inability to attract working classes and other socio-economic strata of society at a wide scale.

Haydeh Ravesh is a former political prisoner

Hamidreza Vasheghanifarahani

We need to see the Jina Uprising as a form of political practice: in other words “it makes a road by walking on it”. Different groups, such as women, ethnic minorities and the working class, have participated in the uprising through explicit protests, living, practising and developing the uprising’s values. They are recognising historical and current injustices and oppression other groups have experienced and are discussing alternatives.

In this sense, the uprising brings together and bridges all moments and practices of resistance and struggle in contemporary Iran. These include the 1979 women’s protests against the Khomeini’s imposition of the hijab or resistance of the Turkmen and Kurdish people in 1979-81, to the 1990s uprisings of the working class and urban poor against structural adjustment policies and the post-2017 uprisings, such as the Tamouz Entefaza of the Arab people in Kuzestan.

The uprising has played a significant role in constructing solidarity lines, which the ideological and repressive apparatus of the regime has tried to prevent through acts of repression, such as the massacre of leftist political prisoners in the 1980s, ethnic cleansing, censorship, serial murders of intellectuals in the 1990s, and imprisonment of political activists and citizens over the last four decades.

This uprising also represents a break with the past. It abandoned the political discourse in which the regime was able to present its own major factions (the Principalists and the Reformists) as the only possible political alternatives.

The uprising detached political discourse from the reductionist notion that neglects intersectionality and the matrix of oppression.

It explicitly brought issues of women, queer community, ethnic communities and population and the environment into the struggle and provided a shared ground for demands of different movements and post-1979 uprisings, from the 1990 urban poor uprising to Bloody November (2019), and from the Kurdish movement to the women’s movement.

It revealed the diverse and multi-directional nature of oppression of the patriarchal Farshi’ist (Fars ethno-centric and Shi’ist) regime and the exploitation of the working class and nature, discrimination against non-Farsi ethnic minorities, non-Shi’a population and women. On the other hand it has exposed everyday forms of resistance of the oppressed population that have been neglected.

I also want to mention that adolescents have claimed a voice in the Jina Uprising. Sadly, the regime killed more than 70 children. Nevertheless, children and adolescents have challenged their representation as victims by showing courage, participating in demonstrations, chanting in schools, and highlighting their demands to a society that undermines them as immature and irrational.

Women and queer comrades living in Iran are qualified to answer questions about the accuracy of media reports of women changing how they dress in public spaces. I can only say that if many women are not wearing hijab, it does not mean the regime has accepted it or it is a mere change in social behaviour. It is a form of political resistance. The regime has not abandoned the morality police and its repressive measures. When we see pictures in the media of women in the streets not wearing hijab, we see their agency and resistance practised collectively and on a daily basis.

They are still being photographed, threatened and arrested by officers. The regime is also implementing other techniques. It issues closure orders against local shops which allow women to enter without wearing hijab. It hopes it can turn a fraction of the population against another fraction. In addition, many university students are receiving suspension rules from disciplinary committees due to not following the compulsory hijab code.

Above all, the new wave of arrests and the filing of false accusations against activists shows that the situation is not limited to the mainstream media’s representation of what is happening in Iran. Samaneh Asghari, a children’s rights activist, has been arrested again. Sarvenaz Ahmadi has been sentenced to 3 years and six months imprisonment.

The Ministry of Intelligence arrested several citizens and activists in Gilan province and some are still in prison and some have been released on bail waiting for trial. Jafar Ebrahimi, a Board Member of the Coordinating Council of Iranian Teacher Trade Associations (CCITTA), who is in prison with a 5 year sentence, is facing a new case against him. In addition, on the anniversary of Jina’s murder, at least 500 individuals have been arrested in Tehran.

Strikes can play a significant role in overcoming the regime. There is no doubt about this. However, we need to reconsider what we mean by the working class. Many young individuals and women participating in the uprising belong to the working class. I am not simply referring to their working-class background. They are workers and employed in waged labour and with precarious conditions. Nevertheless, they tend to organise themselves in the streets instead of in the workplace.

Secondly, many organised working-class groups have participated in the uprising. Teachers showed solidarity with the uprising through strikes and issuing solidarity statements. They resisted the authorities’ demands to hand over lists of students participating in the uprising or reveal school CCTV footage. During their strikes for their labour rights, oil industry workers also issued solidarity statements.

In Rojhilat, or Eastern Kurdistan, the Kurdish Region within the borders of Iran, several public strikes have taken place during the last 12 months. The latest one was in mid-September in the memory of Jina Amini.

Thirdly, we need to bear in mind that people have basic needs. In a condition where inflation is high and wages are extremely low, it is unrealistic to expect workers to go on strike easily. They need to earn to survive. This does not mean they do not care about the uprising. As I said, many have already shown their solidarity and participation.

Strikes also require organisation. Any working class attempt to organise itself has been suppressed harshly for decades. Yet, several organisations have been constructed through the years despite the repression. Considering the dynamics of Iran’s context, we need to have realistic expectations in this regard and understand the uprising as a praxis developing itself.

Hamid Vasheghanifarahani is a childrens’ rights activist

Fariba Balouch

One year has passed in the life of the Woman Life Freedom movement. One year has passed since Jina Amini died. One year since we promised ourselves we could take away these mourning clothes the government imposed on us.

One year since a minority girl not from Tehran lost her life for the crime of being ‘immodest’. Now a single Kurdish woman has become a hero of the revolution. Iranian history is divided now into before and after her death. And we promise ourselves again we will stand until the end of the dictatorship.For one year now women and men in Baluchistan every single Friday have been protesting.

Many have been killed. 500 have serious injuries. No harassment from the government, no bullets, no guns, can stop them. The Baluchis have lives, they have families, they have dreams. They want respect and freedom. They want to exist. They are frightened too but they are brave and now you can hear them. You can hear the voice of freedom every Friday from Baluchistan.

It’s been decades and the kids don’t have schools or access to water. They work from seven years old. They have no ID. They have no existence in the eyes of the government. At an early age you become the only breadwinner and then the government kills you.

You still hear their strong voices because they’ve suffered injustice for years. For the first time we can hear them because of the Women Life Freedom movement. The revolution became a revolution for those who were always marginalised. For the first time Iranians see the singing and dancing of the Baluchi people.

For 40 years we’ve been branded as terrorists and violent. It’s the first time we are hearing the voices of Baluchis. This is an achievement of the Women Life Freedom movement. And the Baluchi people are now hopeful. On Friday as well they’re asking for justice, and will our children finally become Iranian citizens, and will we have bread, water. And schools, and have some respect.

Generations have suffered injustice, but now for the first time we see we are seen, and this movement is the movement for all of those who were not seen. And we will carry on because it is not just about Iranians women’s rights it is about all women’s rights and all human rights we are all in it together for humanity.

Fariba Balouch was speaking at the ‘Mahsa Day’ protest on 16 September in London

Pingback: Two years after Jina’s murder: ‘the movement in Iran isn’t dead, it has changed’ | MENA Solidarity Network